Huxley’s Nightmare: Falling IQs and the Decline of Reading

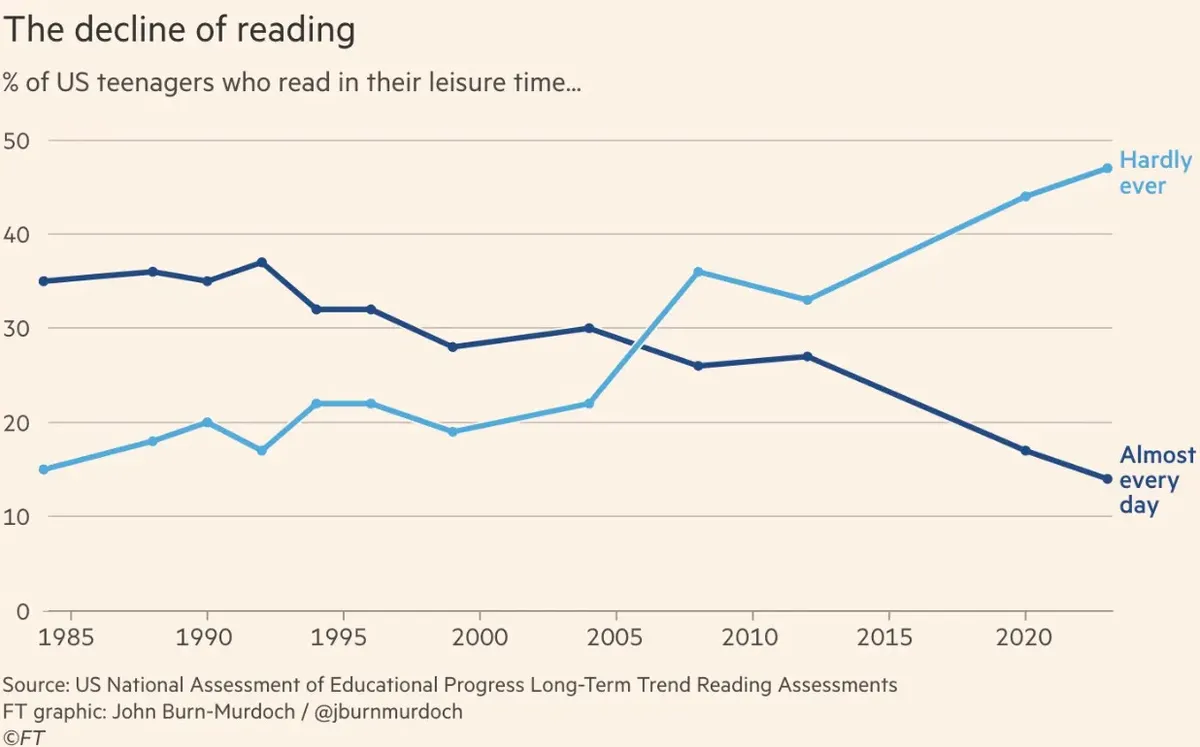

Throughout the 20th century, people were getting smarter. This trend became known as the “Flynn Effect” after the political scientist James Flynn who observed that IQ scores rose about three points per decade. However, this observation no longer holds. In many Western countries, IQ scores have begun to fall, and functional literacy is reversing a trend of growth that dates back to the Industrial Revolution.

Researchers are calling this the “Reverse Flynn Effect,” and a leading hypothesis for its cause is the displacement of reading by digital media. The reversal began around 2010, right when smartphones became universal. And the sharpest declines appear among 18-to-22-year olds, which is the group that spends the most time on their phones.

The idea that digital media is making us dumber isn’t new. Neil Postman made a version of this argument forty years ago in his book Amusing Ourselves to Death. He reminded us of the distinction between the two great 20th-century dystopias: George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. While Orwell feared a future where books were banned, Huxley feared a future where no one would want to read them. Postman argued that Huxley was the truer prophet. We are not being oppressed by a Big Brother but sedated by the “soma” of mindless entertainment.

Postman’s core claim was that reading changes how people think. “To engage with the written word means to follow a line of thought, which requires considerable powers of classifying, inference-making and reasoning,” he wrote. In a culture dominated by print, public discourse inherits this structure and is characterized by a coherent, orderly arrangement of ideas. It is no accident that the Age of Reason grew in tandem with the printing press.

Short-form video, by contrast, must be brief and avoid complexity to hold a viewer’s attention. It rewards visceral emotion and unevidenced assertion while punishing the slow labor of logical argument. The result is a dangerous illusion of knowledge. We know everything that happened in the last twenty-four hours but rarely understand the underlying causes or broader context.

Postman’s claims find support in both history and neuroscience. In The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe, Elizabeth Eisenstein documents how the printing press catalyzed the Renaissance and the rise of modern science. In The Weirdest People in the World, Harvard professor Joseph Henrich argues that reading rewires the brain itself. Highly literate societies possess thicker corpus callosa (the nerve fibers connecting the brain’s hemispheres) than those with low literacy, and these biological differences emerge even between genetically indistinguishable populations.

For most of history, this cognitive transformation was a luxury limited to elites. But that changed in the 16th century after Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the Castle Church door in Wittenberg, Germany. At the heart of the Protestant Reformation was sola scriptura: the idea that individuals should develop a personal relationship with God by reading and interpreting the Bible themselves, rather than relying on the authority of priests. This meant everyone had to learn to read.

Luther translated the Bible into German and pressured rulers to take responsibility for literacy and schooling, starting with his own principality of Saxony. As dukes and princes across the Holy Roman Empire adopted Protestantism, they often used Saxony as their model. Over time, literacy and schools spread with the new faith.

When the Reformation reached Scotland in 1560, it established the principle of free public education for the poor. By 1633, it implemented the world’s first local school tax. Within a few generations, this small country produced an outsized number of influential thinkers, including David Hume and Adam Smith. The subsequent intellectual dominance of this tiny region in the 18th century would inspire Voltaire to write: “We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization.”

By 1900, Protestant countries like Britain, Sweden, and the Netherlands reached nearly 100% literacy, while Catholic nations like Spain and Italy lagged at about 50%. When I read this, I was reminded of the criticism Kenneth Clark received for his “Northern” bias and the omission of Spain in his book Civilisation. “The assignment was ‘civilisation,’ and when one asks what Spain has done to elevate mankind, the answer is less clear,” Clark replied bluntly. “Spain simply remained Spain and it was largely a repressive regime.”

Of course there’s more to the story of Protestantism than literacy; it influenced people’s self-discipline, patience, and sociality too. But as Henrich writes, “sola scriptura likely energized innovation and laid the groundwork for standardizing laws, broadening the voting franchise, and establishing constitutional governments.”

Rising literacy and the invention of the printing press sparked the greatest transfer of knowledge to the common person in history. Ambitious minds could now reach far beyond the limitations of their teachers and often bypassed the classroom entirely. A 17-year-old James Watt, for example, taught himself German and Italian to read Jacob Leupold’s 10-volume encyclopedia of engineering and foundational treatises on mechanics like Giovanni Branca’s Le Machine. This self-directed study gave him the technical foundation to re-engineer the steam engine and catalyze the Industrial Revolution, proving that the movement was fueled as much by reading as it was by coal and iron.

We see a similar pattern in the architects of the American Republic. In Thomas Ricks’s book First Principles, I was struck by how critical the reading habits of the Founding Fathers were to the formation of the United States. George Washington modeled his stoic leadership on the life of Cato described in Plutarch’s Lives. John Adams was a lifelong devotee of the Roman orator Cicero, which shaped his view that human nature is inherently ambitious and governments must be structured as a “mixed” system to restrain that ambition. Thomas Jefferson preferred the Greeks over the Romans and was particularly influenced by the writings of Epicurus; this Epicurean influence is evident in the “pursuit of happiness” ideal he enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. Most critically, James Madison prepared for the Constitutional Convention with a legendary reading marathon that formed the basis of the Virginia Plan. He asked Jefferson to send him crates of books from Paris on ancient confederacies, such as the Lycian and Amphictyonic leagues. The conclusion Madison drew from his reading was that ancient republics collapsed because they lacked strong central structures and were vulnerable to factions. However, he knew a strong central government could itself become a threat which led him to design a Constitution of checks and balances that would “pit ambition against ambition.”

If one habit unites the leaders, inventors, scientists, and artists who have forged our civilization, it is reading. Serious readers are disproportionately represented in almost every area of human achievement.

Charles Darwin maintained a reading diary that logged an average of one book every 10 days for more than two decades. Benjamin Franklin claims he became a vegetarian as a teenager to save money for more books. Abraham Lincoln’s stepmother said he “read all the books he could lay his hands on,” and Thomas Edison — who had almost no formal schooling — tried to read his way through the Detroit Public Library shelf by shelf. This is why Andrew Carnegie eventually dedicated his fortune to building 2,500 libraries; he wanted to replicate the “treasure” he found as a boy when he was allowed to access the private library of Colonel James Anderson. He knew that reading was the ultimate shortcut to a great mind.

As reading declines, there’s an uncomfortable question we have to ask: How many world-shaping minds are quietly atrophying in front of a screen instead of being sharpened by a page?

The risk isn’t just that we lose a few exceptional individuals though; we also might be losing the cognitive infrastructure required for a free society.

“Democracy is the most difficult of all forms of government, since it requires the widest spread of intelligence,” Will and Ariel Durant wrote in The Lessons of History. It only works if a large share of the population can follow arguments, evaluate claims, and tolerate complexity. These aren’t innate abilities but skills that are learned over time, and reading has long been how people cultivate them.

When reading is displaced by short-form video, public discourse changes. Reason gives way to emotion. Confidence and charisma matter more than coherence. Mobs replace debate. And gradually we regress to the mystical thinking habits of pre-literate, “oral” societies.

As in the world before widespread literacy, an elite few accumulate power, wealth, and knowledge while an angry and divided public senses something is wrong but lacks the tools to understand, criticize, or change it.

This slow erosion of critical thinking was what worried Aldous Huxley most.

After reading 1984, Huxley wrote George Orwell a letter explaining why he thought Orwell’s dystopia was unlikely. Force, he argued, would be unnecessary. Power could be maintained more efficiently by making people love their servitude. In Brave New World, the tool was soma. Today, it might be something far more mundane: an endless stream of mindless entertainment that rewards cognitive passivity.

It has long been observed that domesticated animals like sheep, pigs, and dogs have smaller brains than their wild ancestors. As their environment changed, their cognitive capabilities atrophied. We may be running a similar experiment on ourselves.

Reading built the modern world. It gave us our science, our technology, and our freedom. If we stop valuing it, we shouldn’t be surprised if our world starts to more closely resemble a pre-literate society.

Sources & Further Reading

- Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman

- The Printing Press as an Agent of Change by Elizabeth Eisenstein

- The WEIRDest People in the World by Joseph Henrich

- The Lessons of History by Will & Ariel Durant

- 1984 by George Orwell

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- Aldous Huxley’s 1949 Letter to George Orwell

- First Principles by Thomas Ricks

- Civilisation by Kenneth Clark